Section 11: Conflict and Negotiation

Describe why conflict resolution, “crucial conversations,” and other higher stakes communication is necessary to study in organizations

The moment there were two automobiles on the highway, there was a potential for a vehicle crash. This is true not only of the network of open roads, but also in an organization, where just two employees can just as easily “crash” in some sort of conflict.

No matter what the size of the business, conflict is going to be a natural part of its existence. So, naturally, we need to understand how to dissect and navigate conflict and be prepared to have those conversations that lead to conflict resolution. Otherwise, conflict could result in a stalemate that stifles the purpose of the organization.

Learning Outcomes

- Define conflict

- Differentiate among types of conflict

- Identify stages of the conflict process

- Discuss the appropriate use of various conflict management styles

- Identify organizational sources of conflict

What Is Conflict?

The word “conflict” tends to generate images of anger, fighting, and other ugly thoughts that leave people bruised and beaten. Conflict isn’t uncommon in the workplace, and it isn’t always good. But it isn’t always a bad thing, either. Let’s talk a little bit about what conflict is and how we think about it.

Conflict is a perception—meaning it only really exists if it’s acknowledged by the parties that are experiencing it. If Teresa and Heitor have a heated discussion about the path the company should take to win more customers, but they walk away from the disagreement unfazed and either don’t think about the issue again or think the issue is resolved, then no conflict exists. If Teresa and Heitor both walk away feeling that their ideas weren’t heard by the other, that the other is wrong, that the other needs to come around to a better point of view . . . then conflict exists.

Conflict is a perception—meaning it only really exists if it’s acknowledged by the parties that are experiencing it. If Teresa and Heitor have a heated discussion about the path the company should take to win more customers, but they walk away from the disagreement unfazed and either don’t think about the issue again or think the issue is resolved, then no conflict exists. If Teresa and Heitor both walk away feeling that their ideas weren’t heard by the other, that the other is wrong, that the other needs to come around to a better point of view . . . then conflict exists.

Teresa’s and Heitor’s situation could be viewed as a competition rather than conflict. Some people use competition and conflict interchangeably; however, while the terms are similar, they aren’t exactly synonymous. Competition is a rivalry between two groups or two individuals over an outcome that they both seek. In a competition there is a winner and a loser. Teresa might want to attract more customers by a direct mail campaign and Heitor may be championing a television campaign. They may be competing for a finite amount of marketing budget, and if Heitor’s idea is rewarded, then he is the competition’s winner. Teresa is the loser. They may shake hands after the fact, shrug it off and go on to compete another day.

Conflict is when two people or groups disagree, and the disagreement causes friction. One party needs to feel that the other’s point of view will have a negative effect on the final outcome. Teresa may feel strongly about direct mail campaigns because she’s done several with great results. Heitor may feel television is the way to go because no one reads their mail anymore—it just gets thrown out! Each of them may feel that the other’s approach is a waste of the marketing budget and that the company will not benefit from it. Teresa will jump in and prevent Heitor from trying to further his goal for television advertising, and Heitor will do the same to Teresa.

Conflict can be destructive to a team and to an organization. Disadvantages can include:

- Teams lose focus on common goals

- Winning eclipses any other goals of the group

- Judgement gets distorted

- There is a lack of cooperation

- Losing members lack motivation to continue participation

But if managed well, conflict can be healthy and spark creativity as parties try to come to consensus. Some of the benefits of conflict include:

- High energy

- Task focus

- Cohesiveness within the group

- Discussion of issues

There has been plenty of conflict over how conflict is viewed in the workplace over the years. Just like our concept of teams, our concepts of managing people and how they’re motivated, our concepts of stress in the workplace have changed as we’ve learned.

Practice Question

Traditional View

Early in our pursuit of management study, conflict was thought to be a dysfunctional outcome, a result of poor communication and lack of trust between co-workers. Conflict was associated with words like violence and destruction, and people were encouraged to avoid it at all costs.

This was the case all the way up until the 1940s, and, if you think about it, it goes right along with what we thought we knew about what motivated people, how they worked together and the structure and supervision we thought we needed to provide to ensure productivity. Because we viewed all conflict as bad, we looked to eradicate it, usually by addressing it with the person causing it. Once addressed, group and organization would become more productive again.

Many of us still take the traditional view—conflict is bad and we need to get rid of it – even though evidence today tells us that’s not the case.

The Human Relations View

Since the late 1940s, our studies of organizational behavior have indicated that conflict isn’t so thoroughly bad. We came to view it as a natural occurrence in groups, teams and organizations. The Human Relations view suggested that, because conflict was inevitable, we should learn to embrace it.

But they were just starting to realize, with this point of view, that conflict might benefit a group’s performance. These views of dominated conflict theory from the late 1940s through the mid-1970s.

The Interactionist View

In the Interactionist View of conflict, we went from accepting that conflict would exist and dealing with it to an understanding that a work group that was completely harmonious and cooperative was prone to becoming static and non-responsive to needs for change and innovation. So this view encouraged managers to maintain a minimal level of conflict, a level that was enough to keep the group creative and moving forward.

The Interactionist View is still viable today, so it’s the view we’re going to take from here on as we discuss conflict. We know that all conflict is both good and bad, appropriate and inappropriate, and how we rate conflict is going to depend on the type of conflict. We’ll discuss types of conflict next.

Types of Conflict

In literature, fledgling writers learn that there are many different kinds of conflict that arise in literature. One might see a plot that outlines the “man vs. man” scenario, and another might be “man vs. nature.” When examining workplace conflict, one sees that there are four basic types, and they’re not terribly different from those other conflicts you learned in freshman literature except that they all deal with conflict among people. They are:

- Intrapersonal

- Interpersonal

- Intragroup

- Intergroup

Intrapersonal Conflict

The intrapersonal conflict is conflict experienced by a single individual, when his or her own goals, values or roles diverge. A lawyer may experience a conflict of values when he represents a defendant he knows to be guilty of the charges brought against him. A worker whose goal it is to earn her MBA might experience an intrapersonal conflict when she’s offered a position that requires her to transfer to a different state. Or it might be a role conflict where a worker might have to choose between dinner with clients or dinner with family.

Interpersonal Conflict

As you might guess, interpersonal conflict is conflict due to differences in goals, value, and styles between two or more people who are required to interact. As this type of conflict is between individuals, the conflicts can get very personal.

Jobs v Sculley

Apple is a global brand; in fact, its reach is so prevalent you’re most likely in the same room as at least one Apple product. However, it wasn’t always such a strong contender in the market.

When MacIntosh sales didn’t meet expectations during the 1984 holiday shopping season, then-CEO of Apple John Sculley demanded that Steve Jobs be relieved of his position as vice president of the MacIntosh department. Cue interpersonal conflict. As Steve Jobs was still chairman of Apple’s board, it was Sculley’s wish that Jobs represent Apple to the outside world without any influence on the internal business. Steve Jobs got wind of this and tried to sway the board in his favor. The conflict was put to an end by the board when they voted in favor of Sculley’s plan. Jobs ended up leaving the company, disclosing that hiring Sculley for the CEO position was the worst mistake he ever made.

However, Jobs went on to found the company NeXT (a computer platform development company), and when in 1997 NeXT and Apple merged, Jobs retook control of Apple as its CEO, where he remained until he resigned in 2011 because of health issues. Steve Jobs was largely responsible for revitalizing Apple and bringing it to be one of the “Big Four” of technology, alongside Google, Amazon, and Facebook.

Intragroup Conflict

Intragroup conflict is conflict within a group or team, where members conflict over goals or procedures. For instance, a board of directors may want to take a risk to launch a set of products on behalf of their organization, in spite of dissenting opinions among several members. Intragroup conflict takes place among them as they argue the pros and cons of taking such a risk.

Intergroup Conflict

Intergroup conflict is when conflict between groups inside and outside an organization disagree on various issues. Conflict can also arise between two groups within the same organization, and that also would be considered intergroup conflict.

Within those types of conflict, one can experience horizontal conflict, which is conflict with others that are at the same peer level as you, or vertical conflict, which is conflict with a manager or a subordinate.

Practice Question

Creating good conflict is a tough job, and one that’s not often done right. But organizations that don’t encourage dissent won’t be around for very long in today’s world. Companies today go out of their way to create meetings where dissension can occur, reward people who are courageous enough to provide alternative points of view, and even allow employees a period of time to rate and criticize management.

The Conflict Process

The conflict process—that is, the process by which conflict arises—can be seen in five stages. Those stages are:

- Potential opposition or incompatibility

- Cognition and personalization

- Intentions

- Behavior

- Outcomes

Potential Opposition or Incompatibility

The first stage in the conflict process is the existence of conditions that allow conflict to arise. The existence of these conditions doesn’t necessarily guarantee conflict will arise. But if conflict does arise, chances are it’s because of issues regarding communication, structure, or personal variables.

- Communication. Conflict can arise from semantic issues, misunderstanding, or noise in the communication channel that hasn’t been clarified. For instance, your new manager, Steve, is leading a project and you’re on the team. Steve is vague about the team’s goals, and when you get to work on your part of the project, Steve shows up half the way through to tell you you’re doing it wrong. This is conflict caused by communication.

- Structure. Conflict can arise based on the structure of a group of people who have to work together. For instance, let’s say you sell cars, and your co-worker has to approve the credit of all the people who purchase a vehicle from you. If your co-worker doesn’t approve your customers, then he is standing between you and your commission, your good performance review, and your paycheck. This is a structure that invites conflict.

- Personal variables. Conflict can arise if two people who work together just don’t care for each other. Perhaps you work with a man and you find him untrustworthy. Comments he’s made, the way he laughs, the way he talks about his wife and family, all of it just rubs you the wrong way. That’s personal variable, ripe to cause a conflict.

Cognition and Personalization

In the last section, we talked about how conflict only exists if it’s perceived to exist. If it’s been determined that potential opposition or incompatibility exists and both parties feel it, then conflict is developing.

If Joan and her new manager, Mitch, are having a disagreement, they may perceive it but not be personally affected by it. Perhaps Joan is not worried about the disagreement. It is only when both parties understand that conflict is brewing, and they internalize it as something that is affecting them, that this stage is complete.

Intentions

Intentions come between people’s perceptions and emotions and help those who are involved in the potential conflict to decide to act in a particular way.

One has to infer what the other person meant in order to determine how to respond to a statement or action. A lot of conflicts are escalated because one party infers the wrong intentions from the other person. There are five different ways a person can respond to the other party’s statements or actions.

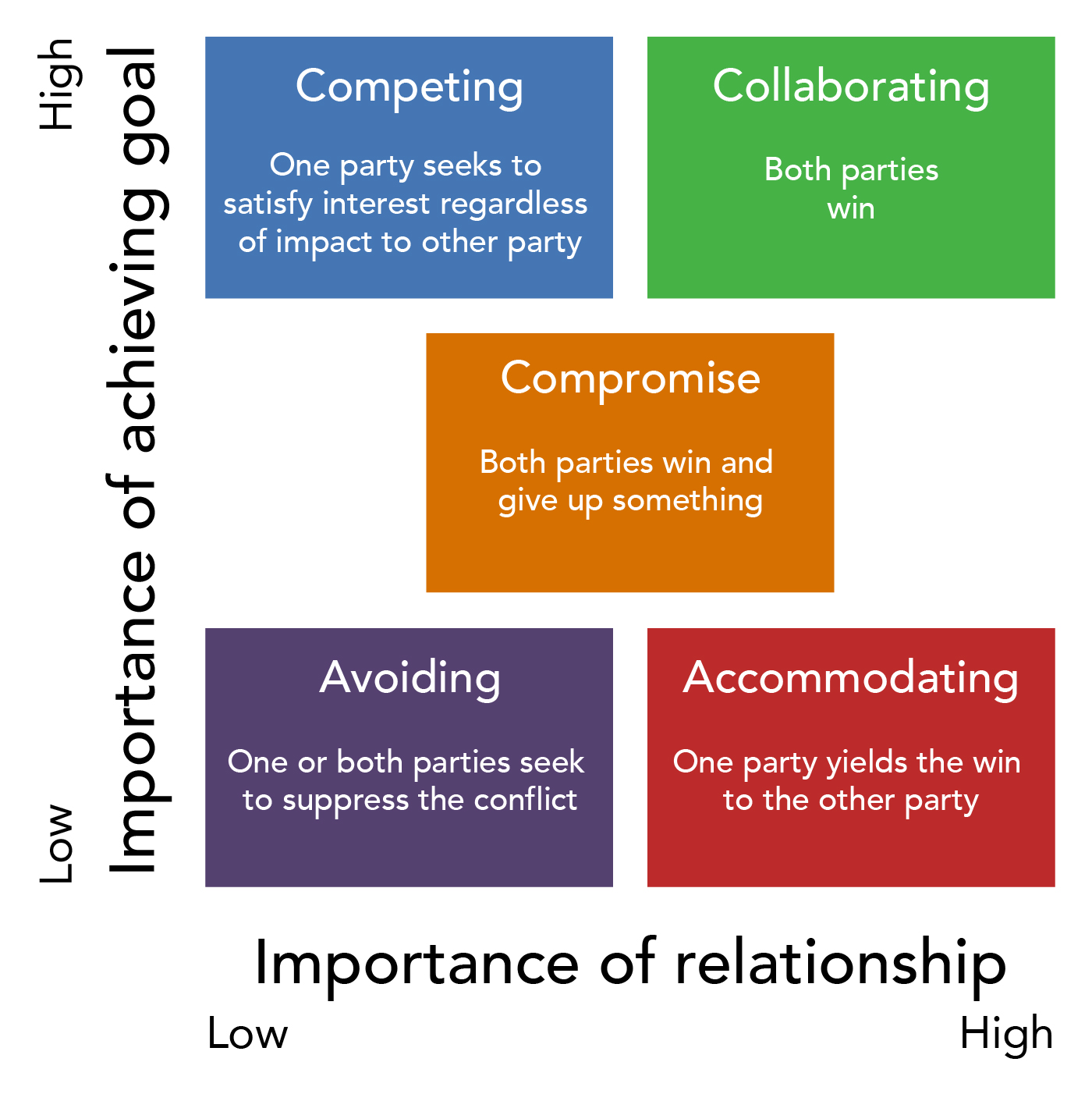

- Competing. One party seeks to satisfy his own interests regardless of the impact on the other party.

- Collaborating. One party, or both, desire to fully satisfied the concerns of all parties involved in the conflict.

- Avoiding. One party withdraws from or suppresses the conflict once it is recognized.

- Accommodating. One party seeks to appease the opponent once potential conflict is recognized.

- Compromising. Each party to the conflict seeks to give up something to resolve the conflict.

We’ll talk about this a little more in the next section when we use these styles to manage conflict.

Behavior

Behavior is the stage where conflict becomes evident, as it includes the statements, actions and reactions of the parties involved in the conflict. These behaviors might be overt attempts to get the other party to reveal intentions, but they have a stimulus quality that separates them from the actual intention stage.

Behavior is the actual dynamic process of interaction. Perhaps Party A makes a demand on Party B, Party B argues back, Party A threatens, and so on. The intensity of the behavior falls along a conflict oriented continuum. If the intensity is low, the conflict might just be a minor misunderstanding, and if the intensity is high, the conflict could be an effort to harm or even destroy the other party.

Outcomes

Outcomes of a conflict can be either functional or dysfunctional:

- Functional outcomes occur when conflict is constructive. It may be hard to think of times when people disagree and argue, and the outcome is somehow good. But think of conflict, for a moment, as the antidote to groupthink. If group members want consensus, they’re bound to all agree before all the viable alternatives have been reviewed. Conflict keeps that from happening. The group may be close to agreeing on something, and a member will speak up, arguing for another point of view. The conflict that results could yield a positive result.

- Dysfunctional outcomes are generally more well known and understood. Uncontrolled opposition breeds discontent, which acts to sever ties and eventually leads to the dissolution of the group. Organizations meet their ultimate demise more often than you’d think as a result of dysfunctional conflict. People who hate each other and don’t get along can’t make decisions to run a company well.

Practice Question

Managing conflict in today’s business world is a must. We’ll look next at how that’s done.

Conflict Management Styles

We talked earlier about the “intentions” stage of conflict when we discussed how conflict develops. The intentions stage discusses how each player in the conflict interprets the statements and actions of the other conflict participant, and then the reaction that they give. Those reactions are the basis for conflict management.

Whether you’re managing the conflict of two subordinates or embroiled in the midst of your own conflict, you make a choice on how the conflict should be managed by weighing the importance of the goal against the importance of the relationships in questions.

Each person brings his own innate style of conflict management to the party. Are they all right or all wrong? Let’s look at Teresa and Heitor’s situation once more—they’re charged with the task of bringing new customers to their business. Teresa wants to use direct mail to bring attention to their company’s offerings, and Heitor wants to move forward with an expensive television ad campaign. Teresa thinks that Heitor is wasting dollars by putting the message out there for an untargeted audience of viewers, and Heitor thinks that Teresa is wasting dollars by sending something out that’s just going to get tossed in the trash.

The avoiding style of conflict resolution is one where one has low concern for his or her ultimate goal and low concern for his or her relationship with the other. In this situation, Heitor might avoid any discussion with Teresa, not wanting to start any fights. He’s just not that kind of guy. But his idea isn’t getting furthered along, nor is hers, nor is the company meeting its goals. The conflict hasn’t gone away, and the job just isn’t getting done.

The accommodating style of conflict resolution is where one party focuses on the needs of the other, and not the importance of the goal. If Heitor were one to adopt the accommodating style, he might look at Teresa as a valued team player who really needs a break after a couple of tough months. Without thought to the goal and the outcome the company expects, he tells Teresa to go ahead with the direct mail program.

The competing style of conflict resolution is defined by one party pushing ahead with his or her own mission and goals with no concern for the other party in the conflict. If Teresa were to adopt the competing style of conflict resolution, she might move forward with the plan to use direct mail and ignore anything to do with Heitor’s suggestion. She’d take her idea to their boss and implement and run right over any objections Heitor had. As you might guess, this approach may exacerbate other conflicts down the road!

Right in the middle of Figure 1 is the compromising style of conflict management. Here, moderate concern for others and moderate concern for the ultimate goal are exhibited, and a focus is placed on achieving a reasonable middle ground where all the parties can be happy. For Heitor and Teresa, this might mean a joint decision where they devote half of their marketing funds to the direct mail campaign that Teresa wants to do, and the other half to the television spots that Heitor wants to do. Neither party has gotten exactly what he or she wanted, but neither party is completely dissatisfied with the resolution.

Finally, the collaborating style is one where there is high concern for relationships and high concern for achieving one’s own goal. Those with a collaborating style look to put all conflict on the table, analyze it and deal openly with all parties. They look for the best possible solution: a win for each party in the conflict. In this situation, Heitor and Teresa would sit down, look at the possible conversion rate of each of their planned marketing campaigns. Perhaps they would find that a third option—online advertising—would provide a more targeted audience at a discounted price. With this new option that both parties could get behind, conflict is resolved and both feel like the company’s goal will be satisfied.

For Teresa and Heitor, the conditions were right for a collaborating style of conflict resolution, but it’s easy to see how a different style might have been more appropriate if the situation had been different.

Practice Question

So, now we understand what conflict is, how it develops and how to respond. We’re ready to face conflict when we find it! But…where will we find it? Where, within an organization, does conflict lurk?

Sources of Conflict in an Organization

Personality conflicts make work rough. When you’re not in the office, you get to choose who you hang out with, but during the work day, the cast of characters is chosen for you. If an organization is looking to hire people that fit with the company culture, then chances are good you’ll get along with most of them! However, it’s likely that there will be at least one coworker that you don’t get along with 100 percent.

Organizational sources of conflict are those events or factors that cause goals to differ. Personality conflicts, irritating as they may be, don’t actually qualify as an organizational source of conflict. They may be the most aggravating part of your day and, certainly, they’re something organizations need to watch for if it interferes with daily work, but these organizational sources produce much bigger problems. Those sources are

- Goal incompatibility and differentiation

- Interdependence

- Uncertainty and resource scarcity

- Reward systems

Goal Incompatibility and Differentiation

Organizational sources of conflict occur when departments are differentiated in their goals. For instance, the research and development team at an electronics company might be instructed to come up with the best new, pie-in-the-sky idea for individual-use electronics—that thing consumers didn’t know they needed. The R&D team might come up with something fantastic, featuring loads of bells and whistles that the consumer will put to excellent use.

Organizational sources of conflict occur when departments are differentiated in their goals. For instance, the research and development team at an electronics company might be instructed to come up with the best new, pie-in-the-sky idea for individual-use electronics—that thing consumers didn’t know they needed. The R&D team might come up with something fantastic, featuring loads of bells and whistles that the consumer will put to excellent use.

Then, the manufacturing team gets together to look at this new design. They’ve been told that management likes it, and that they need to build it by the most economical means possible. They start make adjustments to the design, saving money by using less expensive materials than what were recommended by the R&D team. Conflict arises.

Goal incompatibility and differentiation is a fairly common occurrence. The manufacturing team disagrees with research and development. The sales department feels like the legal department is there to keep them from getting deals signed. Departments within the organization feel like they are working at cross-purposes, even though they’re both operating under the assumption that their choices are best for the company.

Interdependence

Interdependence describes the extent to which employees rely on other employees to get their work done. If people all had independent goals that didn’t affect one another, everything would be fine. That’s not the case in many organizations.

For instance, a communication department is charged with putting together speaking points that help their front-line employees deal with customer questions. Because the communications department is equipped to provide clear instructions but are not necessarily the subject matter experts, they must wait for engineering to provide product details that are important to the final message. If those details are not provided, the communication department cannot reach their goal of getting these speaking points out on time for their front-line staff to deal with questions.

The same holds true for a first-, second-, and third-shift assembly line. One shift picks up where another leaves off. The same standards of work, production numbers, and clean-up should be upheld by all three teams. If one team deviates from those standards, then it creates conflict with the other two groups.

Uncertainty and Resource Scarcity

Change. We talked about it as a source of stress, and we’re going to talk about it here as an organizational source of conflict. Uncertainty makes it difficult for managers to set clear directions, and lack of clear direction leads to conflict.

Resource scarcity also leads to conflict. If there aren’t enough material and supplies for every worker, then those who do get resources and those who don’t are likely to experience conflict. As resources dwindle and an organization has to make do with less, departments will compete to get those resources. For instance, if budgets are slim, the marketing department may feel like they can make the most of those dollars by earning new customers. The development team may feel like they can benefit from the dollars by making more products to sell. Conflict results over resource scarcity.

Reward System

An organization’s reward system can be a source of conflict, particularly if the organization sets up a win-lose environment for employee rewards.

For instance, an organization might set a standard where only a certain percent of the employees can achieve the top ranking for raises and bonuses. This standard, not an uncommon practice, creates heavy competition within its employee ranks. Competition of this nature often creates conflict.

For instance, an organization might set a standard where only a certain percent of the employees can achieve the top ranking for raises and bonuses. This standard, not an uncommon practice, creates heavy competition within its employee ranks. Competition of this nature often creates conflict.

Other forms of rewards that might incite conflict include employee of the month or other major awards that are given on a competitive basis.

Conflict can occur between two employees, between a team of employees, or between departments of an organization, brought about by the employees, teams, or organizations themselves. Now that we understand conflict, we’re ready to take on negotiation. It’s different from conflict, but it’s easy to see how some of the skills one uses to be a great negotiator are snatched from conflict resolution.

Practice Question

CC licensed content, Original

- Conflict Management. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Activity: Conflict Management Styles. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://lumenlearning.h5p.com/content/1290662787165074178. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Five primary styles of conflict management. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

Practice: Conflict Management. Authored by: Barbara Egel. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

CC licensed content, Specific attribution

- Untitled. Authored by: mohamed Hassan. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/vectors/silhouette-relationship-conflict-3141264/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Pixabay License

- Laptop. Authored by: rawpixel. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/photos/laptop-computer-technology-monitor-3190194/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Pixabay License

- Cups. Authored by: qimono. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/cup-champion-award-trophy-winner-1613315/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Pixabay License