Section 8: Communication in the Workplace

What you’ll learn to do: Describe the key components of effective communication in contemporary organizational life

All organizations communicate. They communicate internally with their employees and externally with their stakeholders, their customers, and their communities. Organizations that communicate well—and ethically—are a step ahead of their competitors, because communication is how employees understand an organization’s mission and goals, and how their roles support them.

Communication is more than just a quick conversation or a written memo. Knowing the components of communication, the types of communication, and the barriers of the communication process are key in understanding what good organizational communication should look like.

Learning Outcomes

- Define the functions of organizational communication

- Describe the communication process

- Analyze direction of communication within an organization

- Discuss types of communication within an organization

- Analyze barriers to effective communication

Functions of Organizational Communication

Research tells us that poor communication is the most frequently cited source of interpersonal conflict.1 It’s not surprising, really. We spend about 70 percent of our waking hours engaged in some sort of communication. Whether it’s writing, reading, speaking, or listening, we’re participating in the transference and understanding of meaning between individuals. Those individuals who are good at communicating are setting themselves up for success. Those organizations that facilitate good communication—both inside their walls and with their customers and community—set themselves up for success as well.

In an organization, communication serves four purposes:

- Control

- Motivation

- Information

- Emotional Expression

Control

Organizations have rules and processes that employees must follow, communicated to workers to keep order and equity operating within the system. For instance, if an individual has a grievance about her job task, the organization might dictate that the grievance first has to be addressed with a supervisor. If it goes unresolved, the next step in the process might be to file a complaint that is reviewed by a committee. This is an example of an organization leveraging their communication processes to keep order and ensure grievances are heard fairly.

There’s an informal version of control within an organization, too. A department member might be too eager to please the boss, staying late and producing more than the others on his team. The other team members might pick on that eager individual, make fun of him, and very informally control that person’s behavior.

Motivation

Goals, feedback and reinforcement are among those items communicated to employees to improve performance and stimulate motivation. Organizations are likely to exhibit a bit of the “control” aspect in communicating goals to individual contributors, transferring information via a chain like the management by objective process we discussed in an earlier module. Feedback and reinforcement can also be a formal controlled process (via a mid- or end-of-year performance review, for example) but it can also occur in informal ways. When a manager passes an individual, she might stop and say, “Hey, I heard from Fred today about how well you did presenting to his group. Great job! We’ll try to find other opportunities for you to get in front of a crowd.” That would be an informal version of feedback and reinforcement that acts as a motivator.

Information

Organizations need to keep their employees informed of their goals, industry information, preferred processes, new developments and technology, etc., in order that they can do their jobs correctly and efficiently. This information might come to employees in formal ways, via meetings with managers, news and messaging via a centralized system (like an intranet site), or it could be informal, as when a team member on the assembly line suggests a quicker way to approach a task and gets his coworkers to adopt the method.

Emotional Expression

Communication is the means by which employees express themselves, air their grievances, and interact socially. For a lot of employees, their employment is a primary source of social interaction. The communication that goes on between them is an important part of an organization and often sets the culture of the organization.

There is not one function of organizational communication that’s more important than another—an organization needs to have all four of the functions operating well.

Practice Question

An organization can’t actually communicate, though, can it? Technically and scientifically, no. It’s the organization’s employees that do the communicating and follow the processes on behalf of the organization. So, individual expertise is equally important if an organization is going to have a successful communication function.

Communication is happening between individuals when all parties are engaged in uncovering and understanding the meaning behind the words. It’s not something that one person does alone. When business professionals makes their contribution to the uncovering and understanding process, they should strive to be:

- Clear. Their messages should be easily understood

- Concise. Their messages should feature only necessary information

- Objective. Their messages should be impartial

- Consistent. Their messages, when communicated more than once, should always be the same

- Complete. Their messages should feature all the necessary information

- Relevant. Their messages should have meaning to its receiver

- Understanding of Audience Knowledge. Their messages should consider what the receiver already knows about the situation, and not assume too much or too little

These are the seven pillars, or principals, of business communication. If an individual opens his mouth, puts pen to paper, or picks up a camera to make a video, he should be striving to create a message that meets this criteria.

Why? Well, the point of communication is not to talk. It’s to be understood. When your team understands you, they deliver results. When your customers understand you, they buy. When your manager understands you, she advocates for you and supports you in your career. When organizations communicate well and employees understand their roles and how they fit into the organization’s mission, they succeed.

The Process of Communication

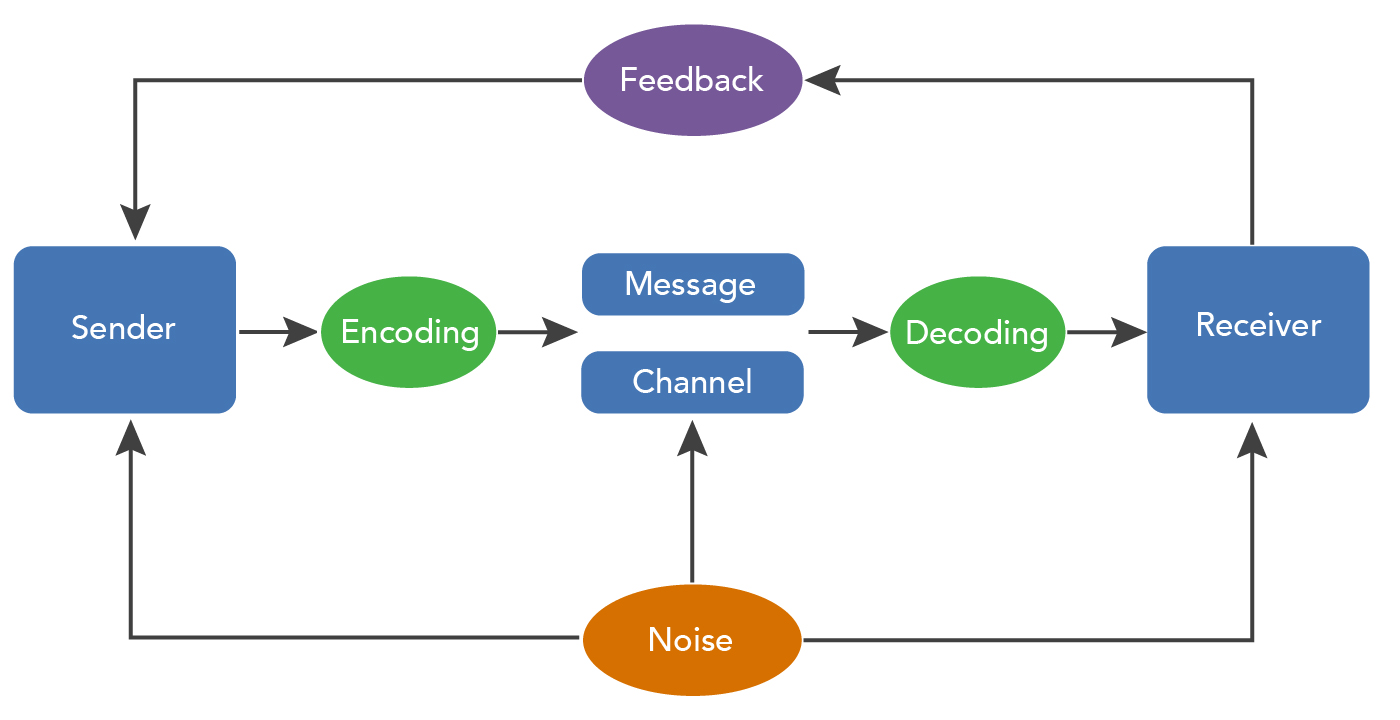

What does communication look like? When you think about communication in its simplest form, the process is really quite linear. There’s a sender of a message—let’s say you—talking. You, the sender, have a thought. You put that thought into words, which is encoding the message.

And then there’s a recipient of a message—in this case, your coworker Nikola. The message comes out of your mouth, and then it is decoded, or processed, by the recipient, Nikola, who then decides on the meaning of your words as a result of that decoding process. She hears your words and considers their meaning—put simply, she’s listening. It looks something like this:

But what the sender says isn’t always what the reciever hears. Encoding and decoding don’t always happen seamlessly. In this instance, Nikola might “tune out” and miss some of what you said, or she may hear your words correctly, but misunderstand their meaning. It may even be a concept that is doomed to be misunderstood before your words are even formed, due to existing difference between you and your coworker. When this happens, it’s called noise.

If Nikola is not clear on your message, she may stop you and say, “Wait. You’re saying this. Do I understand you correctly?” This is called feedback.

Your recipient has let you know that you’ve been misunderstood by giving you feedback. At this point you can

- Repeat the message a second time

- Ask some clarifying questions to determine why your recipient didn’t understand what you said, and then address those issues on your next attempt to communicate your idea.

Feedback can come in a variety of forms, too. In this case, Nikola is repeating your statement and asking for confirmation that she heard it correctly. In another case, you may have told Nikola that to find the restroom she needs to head down a hall and turn right. When she heads down the hall and turns left, that, too, is feedback letting you know you’ve been misunderstood.

Often that’s the kind of feedback an organization has to navigate. Organizations issue a communication, perhaps in the form of a memo, and send it out to all their employees. Employees read it. If the message is understood and appropriate actions are taken, all is well. There may have been noise, but it did not get in the way of the message. If employees start firing emails back to the originator of the message, asking questions or clarifying points, they are engaging in feedback. If they take action that is not appropriate, that’s also feedback. The message needs to be reiterated, framed differently, to clarify portions that were not communicated the first time.

This whole process, the steps between a source and receiver that result in the transference and understanding of meaning, is called the communication feedback loop. In an organizational communication feedback loop, we can also consider the channel of communication in the message. The channel is the medium by which the message travels. Newsletters, one-on-one meetings, town halls, video conferencing—all of these are channels of communication.

Practice Question

There are formal channels of communication in an organization. These are channels of communication established by an organization to transmit messages that impact the work-related activities of its employees. They can follow the authority chain in an organization, and would include things like messages from leadership, information from the human resources department about benefits, or even articles recognizing an employee for great work.

The informal channels of communication in an organization are personal and social. Your mind may automatically go to “water cooler gossip” and, while that is definitely an informal channel of communication, there are plenty of ways informal communication channels do an organization good. For instance, a new process may be in the testing phase with a group of employees. Those employees can iron out the wrinkles of the process and become enthused about it, acting as ambassadors for the new method with other employees before it’s even rolled out. The informal channel, in this example, is communication that will assist with change management.

By understanding the goals of communication and how communication operates, an organization can ensure their employees have the right information to do their jobs, and ultimately open the door to increased engagement and productivity.

Directions of Communication

Now we understand what communication is, and a message is encoded by a sender, decoded by a receiver, all while navigating noise and providing feedback. Organizations communicate to ensure employees have the necessary information to do their jobs, feel engaged, and be productive.

Communication travels within an organization in three different directions, and often the channels of communication are prescribed by the direction in which the communication is flowing. Let’s take a look at the three different directions and types of communication channels used.

Vertical Communication

Vertical communication can be broken down into two categories: downward communication and upward communication.

Downward Communication

Downward communication is from the higher-ups of the organization to employees lower in the organizational hierarchy, in a downward direction. It might be a message from the CEO and CFO to all of their subordinates, their subordinates, and so on. It might be a sticky note on your desk from your manager. Anything that travels from a higher-ranking member or group of the organization to a lower-ranking individual is considered downward organizational communication.

Downward communication might be used to communicate new organizational strategy, highlight tasks that need to be completed, or they could even be a team meeting run by the manager of that team. Appropriate channels for these kinds of communication are verbal exchanges, minutes and agendas of meetings, memos, emails, and even Intranet news stories.

Upward Communication

Upward communication flows upward from one group to another that is on a higher level on the organizational hierarchy. Often, this type of communication provides feedback to organizational leaders about current problems, or even progress on goals.

It’s probably not surprising that “verbal exchanges” are less likely to be found as a common channel for this kind of communication. It’s certainly fairly common between managers and their direct subordinates, but less common between a line worker and the CEO. However, communication is facilitated between the front lines and senior leadership all the time. Channels for upward communication include not only a town hall forum where employees could air grievances, but also reports of financial information, project reports, and more. This kind of communication keeps managers informed about company progress and how employees feel, and it often provides managers with ideas for improvement.

Horizontal Communication

When communication takes place between people at the same level of the organization, like between two departments or between two peers, it’s called horizontal (or lateral) communication. Communication taking place between an organization and its vendors, suppliers, and clients can also be considered horizontal communication.

Even though vertical communication is very effective, horizontal communication is still needed and encouraged, because it saves time and can be more effective—imagine if you had to talk to your supervisor every time you wanted to check-in with a coworker! Additionally, horizontal communication takes place even as vertical information is imparted: a directive from the senior team permeates through the organization, both by managers explaining the information to their subordinates and by all of those people discussing and sharing the information horizontally with their peers.

Not all organizations are set up to facilitate good horizontal communication, though. An organization with a rigid, bureaucratic structure—like a government organization—communicates everything based on chain of command, and often horizontal communication is discouraged. Peer sharing is limited. Conversely, an organic organization—which features a loose structure and decentralized decision making—would leverage and encourage horizontal communication.

Horizontal communication sounds like a very desirable feature in an organization and, used correctly, it is. Departments and people need to talk between themselves, cutting out the “middlemen” of upper management in order to get things done effectively. Unfortunately, horizontal communication can also undermine the effectiveness of downward communication, particularly when employees go around or above their superiors to get things done, or if managers find out after the fact that actions have been taken or decisions have been made without their knowledge.

Practice Question

Now that we understand the three directions in which communication can travel, let’s take a look at types of communication and how they’re employed within an organization.

Types of Communication

Interpersonal Communication

So, now that we know what directions communications travel, how do they get from sender to receiver? Interpersonal communication is how an individual chooses to engage with another individual or group. There are three types of interpersonal communication:

Oral Communication

The chief means of communication is oral, and in most cases, it’s the most effective. Examples of oral communication can be a speech, a one-on-one meeting, or a group discussion.

The primary advantage of oral communication is speed, as the sender of the messages encodes it into words, and a receiver immediately decodes it and offers feedback. Any errors can be corrected before mistakes are made and productivity hindered.

The primary disadvantage of oral communication comes into play whenever the message has to be passed through many people. Did you ever play the game “telephone” with your friends as a child? If you did, you’ll remember that on player starts a message as a whisper at one end, and by the time it reached the other it was often changed, sometimes in a funny way. All laughs aside, that’s a real phenomenon and a real issue in organizations. When messages are verbally passed from person to person, there’s potential for that message to become distorted.

Written Communication

Written communication includes newsletters, memos, email, instant messaging and anything that you type or write. They’re verifiable forms of communication, existing beyond the moment of transmission and something receivers can refer back to for clarification.

The primary advantages of written communications is exactly that—they are written. They exist beyond the moment of transmission and can be used as reference later. Due to their ability to easily be referenced, written communications are particularly good for lengthy, complex communications. Additionally, the process of creating a written communication often requires that the sender be more thorough in his or her communication because there is often enough time to revise and review what’s been written, and to be more careful about the information being transmitted.

A disadvantage of written communication is lack of feedback. Oral communication allows a receiver to respond instantly to the sender with feedback. Written communication doesn’t have a built-in feedback mechanism, and because of that feedback can arrive too late for appropriate action. Another disadvantage of written communication is that it’s time-consuming. Due to the lack of immediate feedback, it’s often a good idea to be more thorough in your written communications, which inevitably takes more time to consider how your words might be unclear and preemptively write in additional context. If a message needs to be communicated quickly, a written communication isn’t always the best solution.

Non-Verbal Communication

It’s not just what you say, it’s how you say it! There’s a myth that says communication is 35% verbal and 65% non-verbal. If that were true, people speaking a foreign language would be much easier to understand. However, it’s very true that non-verbal communication adds additional meaning to in-person conversations. Non-verbal communication includes all of those things that aren’t spoken but definitely transmit part of the message, including the following:

It’s not just what you say, it’s how you say it! There’s a myth that says communication is 35% verbal and 65% non-verbal. If that were true, people speaking a foreign language would be much easier to understand. However, it’s very true that non-verbal communication adds additional meaning to in-person conversations. Non-verbal communication includes all of those things that aren’t spoken but definitely transmit part of the message, including the following:

- facial expressions

- gestures

- proximity to receiver

- touch

- eye contact

- appearance

For instance, your friend may be telling you that she’s really excited about a party she’s planning to attend. But if she appears apathetic and listless, the communication doesn’t come across quite the same. Senders who stand too close to a receiver send a different message than those who keep a socially acceptable distance. Senders who make eye contact appear to be more confident than those who avoid it. And finally, a sender’s general appearance—choice of dress, hygiene, choice of delivery method etc.—can also send a message that either supports or detracts from the verbal message.

Intonation is also a form of non-verbal communication. How you say something, using your tone and inflection, is also reflected in the sender’s message to the receiver. Consider the phrase “How would you like to go to lunch?”

| Emphasized word | Translation |

|---|---|

| How | By what method would you like to go? Car? Bus? |

| you | Someone else is already going to lunch. Would you like to go too? |

| go | Would you like to go out rather than eating in? |

| lunch | Is lunch okay, rather than breakfast or dinner? |

Intonation also includes the level of energy and emotion with which the sender delivers his message. If you’ve seen Gene Wilder’s Willie Wonka in Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, when one of the children visiting the factory engages in a behavior he or she is not supposed to, Willie Wonka delivers a quiet, apathetic, “Stop. Please. Don’t.” The words would indicate Wonka is invested in getting the child to stop, but the tone says something very different.

All these forms of interpersonal communication can take on an upward, downward or lateral direction when one is engaging in communication at work.

Practice Question

Organizational Communication

Communication isn’t just a one-on-one event, where an individual decides to communicate and starts the process. Organizational communication can feature other elements, elements that involve more than one person.

Formal Small-Group Networks

Formal organizations can be very complicated, including groups that feature hundreds of people and multiple hierarchal levels. For the sake of simplicity, we’re going to talk about three of the most common kinds of small groups, and pretend there are five people in each of them. These three common networks are the chain, wheel and all channel.

These diagrams represent communication in a three-level organization, with the dot at the top being the leader, the second tier being mid-level supervisors, and the third tier being subordinates to the mid-level supervisors.

The chain group rigidly follows a chain of command. As you can see, message and communication originates with one person on the chain, and has to travel up and down the line. Communication in a chain network is usually moderate in speed, high in accuracy. The emergence of a leader in this network situation is moderate, and member satisfaction is also moderate. This network feature is common in teams with rigid chains of command.

The wheel group is less rigid. In this type of network, leaders communicate to both levels of their organizations and allow communication from both levels back to them. Communication in a wheel network is fast, because everyone hears the same message, and it’s high in accuracy. The emergence of a leader in this framework is high (because all are looking to the same person) but member satisfaction is often low. This network feature is common in teams with strong leaders.

The all-channel group permits all levels of the group to actively communicate with each other. Communication in an all-channel network is fast, and accuracy is moderate. All-channel groups usually experience no emergence of a leader and member satisfaction is high. This is the common communication framework used in self-managed teams, where all group members participate and no one takes a leadership role.

The effectiveness of any of these networks depends on the variable you’re most concerned about. A wheel structure helps a leader emerge, but if member satisfaction is more important, the all-channel network may be a better choice. No single network is best for all occasions.

Informal Organizational Communication

Of course not all communication in a workplace will be communicated through formal channels. People will gravitate toward individuals they get along better with—whether or not those personal relationships are formed along the organizational structure.

While most companies will have gossip and rumors, these informal conversations can be useful if viewed in the right light. Conversations about gossip and rumors are less about the content of the conversations and more about stress, actually. Rumors fly through the company because they’re important to employees and clear up ambiguity, relieving anxiety. Secrecy about appointing new managers, changing org structures, and so on, help fuel these communications.

Managers can leverage informal communication to get a better handle on the morale of their teams and identify issues that employees find important or are stressed about. It’s a filter and a feedback mechanism that will likely continue to exist no matter what steps are taken to avoid it.

These are ways that people communicate, alone or in groups, within organizations. Whether they’re speaking and interacting face-to-face, or sending a long a memo, they’re exercising very traditional forms of message transmission. But today we have technology to help us communicate, and that changes some of these dynamics quite a bit. We’ll take a look at how technology as affected organizational communication in the next module.

Effective Communication

Understanding the functions, process, direction, and types of communication is the first step toward communicating effectively. But of course, there’s more! Communicating well involves a number of factors, including

- Sending an accurate message

- Removing communication barriers

- Controlling distractions (or noise)

- Monitoring non-verbal cues and actively listening to and offering feedback

Putting together a message, verbally or written, is only the beginning. Let’s take a look at the receiver and the barriers he or she might be experiencing that prevent her from receiving the message clearly.

Perceptual Biases

Perceptual biases can affect how a receiver processes information about others. These biases can allow us to make faster decisions, but they can also lead us to stop gathering information and making decisions prematurely. Those who have already made up their mind stop paying attention.

For example, Theo, a manager, needs to make a decision about a new hire. A talented employee, Susie, refers a friend she thinks would be a good addition to the company and their team. That manager might say, “Well, if this person is okay in Susie’s book, she’s okay with me.” Theo stops gathering information at the point at which he hears Susie’s advice, because Susie is a talented and trusted team member.

However, the person Susie’s recommended turns out to have limited skills and is not a good fit. Theo was a victim of perceptual bias. He took the word of a trusted team member instead of investigating further.

When a sender is transmitting a message, the receiver’s perceptual bias is the “noise” that changes the sender’s meaning. The perceptual bias can be managed by awareness, use of objective data and confirmation whenever possible.

Organizational Barriers

Effective communication can be impacted by an organization’s hierarchical structure and the rules around how information flows upward, downward, and laterally. For instance, a rigid organizational structure might dictate that communication follow a path up and down, from VP to director to manager and back up from manager to director to VP. This hard-and-fast rule may not be ideal for organizations that need to make quick decisions with information generated by lower-level employees.

Effective communication can be impacted by an organization’s hierarchical structure and the rules around how information flows upward, downward, and laterally. For instance, a rigid organizational structure might dictate that communication follow a path up and down, from VP to director to manager and back up from manager to director to VP. This hard-and-fast rule may not be ideal for organizations that need to make quick decisions with information generated by lower-level employees.

Let’s say there were a series of injuries at a manufacturing plant and a company vice president is looking to make changes to ensure worker safety. In a rigid organizational structure, he might ask his direct report, a director, to confirm all the reasons why these injuries are occurring. The director then asks a manager, who asks a team lead, and so on. The process is inefficient.

Organizational hierarchies can also obstruct communication via status differences. Often access to C-level leaders is restricted for lower level employees, so information communicated to and from those levels is often distorted.

Time is also an organizational barrier and an enemy of good communication. Workers are under pressure to perform and meet deadlines, and time may prevent them from communicating with their team members and leaders appropriately.

Often steps must be taken organization-wide in order to overcome these kinds of barriers, effectively placing a value on the communication by allowing employees time to communicate and the space to do so with the audience that needs to receive their messages.

Active Listening

As we said earlier in this module, communication isn’t about talking or writing, it’s about being understood. Communicators on both ends of the social feedback loop should practice active listening. Active listening is the process by which the listener assumes a conscious and dynamic role in the communication process through behavior and action. Active listening looks like this:

You can see in the above model that active listening includes asking open-ended and minimizing distractions, clarifying, paraphrasing, and summarizing. All of these are feedback mechanisms, to ensure that the receiver has heard the message correctly.

This model also includes paying attention to non-verbal cues while the sender is transmitting his message in its recommendation to be attuned to and recognize feelings. The non-verbal cues are particularly important in situations where different cultures are involved. Cultures with high-power distance may be listening but hesitate to ask clarifying questions, which places a bit more responsibility on the sender to ensure the message has been understood. Overall, these active listening practices help deconstruct communication barriers.

Effective Feedback

Communication must be restated and reinforced to ensure no noise is seeping into the message. For instance, if managers set goals for employees, they should be prepared to give those employee feedback on their progress, keeping them on course to reach the finish line.

Positive feedback is always good to share, and negative feedback is a little harder. Both need to be offered if employees are expected to change behaviors. Effective feedback should:

- Be fact-based and timely

- Focus on specific behaviors that are clearly documented, rather than vague statements about personalities or attitudes

- Be job related and professional

- Address behaviors under the control of the person receiving the feedback

The sender should also ensure that the receiver has fully understood the feedback.

Practice Question

Organizations that understand these potential barriers to good communication and know-how to navigate them are likely to be more successful in creating higher levels of employee engagement and productivity.

1 Thomas, Kenneth W. and Warren H. Schmidt. “A Survey of Managerial Interests with Respect to Conflict,” Academy of Management Journal, vol 19, no. 2

- Introduction to Key Components of Communication. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Functions of Organizational Communication. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- The Process of Communication. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Images: Communication Process. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Directions of Communication. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Types of Communication. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Formal Small-Group Networks. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Effective Communication. Authored by: Freedom Learning Group. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Active Listening. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Communication. Authored by: Ivan. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://flic.kr/p/2cFwrXk. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Downward and Upward Communication. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-businesscommunicationmgrs/chapter/writing-the-right-message/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Horizontal Communication. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-businesscommunicationmgrs/chapter/writing-the-right-message/. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Woman, teamwork image. Authored by: rawpixel. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/g8bqFDerlLA. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Unsplash License

- This is about how women talk to another person. Authored by: Gradikaa. Provided by: Unsplash. Located at: https://unsplash.com/photos/x31bLGlH6U0. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Unsplash License

- Untitled. Authored by: kai kalhh. Provided by: Pixabay. Located at: https://pixabay.com/photos/baukegel-shield-cone-pilone-hat-2694486/. License: CC0: No Rights Reserved. License Terms: Pixabay License